Seal hunting

Seal hunting, or sealing, is the personal or commercial hunting of seals. The hunt is currently practiced in five countries: Canada, where most of the world's seal hunting takes place, as well as Namibia, the Danish region Greenland, Norway, and Russia. Canada's largest market for seals is Norway (through GC Rieber AS).[1]

Harp seal populations in the northwest Atlantic declined to approximately 2 million in the early 1970s, prompting stronger regulations. As a result the harp seal population in this area increased steadily until the mid 1990's, and was estimated at 5.9 million (between 4.6 and 7.2 million) in 2004.[2] Harp seals have never been considered endangered. The Marine Animal Response Society estimates the harp seal population in the world is approximately 8 million (between 6.4 and 9.5 million).[3]

As a result of population concerns, hunting is now controlled by quotas based on recommendations from International Council for the Exploration of the Sea (ICES),[4] and in 2007, the Canadian Department of Fisheries and Oceans (DFO) set the "total allowable catch" (TAC) of harp seals at 270,000 per year.[5] The Canadian harp seal hunt is by far the largest.[6] The 2007 catch was 234,000 seals, down from 354,000 the year before. According to data gathered by the European Food Safety Authority,[7] Norway claimed only 29,000 with Russia and Greenland landing 5,476 and 90,000 in 2007 respectively.

It is illegal in Canada to hunt newborn harp seals known as "whitecoats". It is also illegal to hunt young, hooded seals (bluebacks). When the seal pups begin to molt their downy white fur at the age of 12–14 days, they are called "ragged-jacket" and can be commercially hunted.[8] After molting, the seals are called "beaters", named for the way they beat the water with their flippers.[9] The hunt remains highly controversial, attracting significant media coverage and protests each year.[10] Images from past hunts have become iconic symbols for conservation, animal welfare, and animal rights advocates. In 2009, Russia banned the hunting of harp seals less than one year old.

Contents |

History

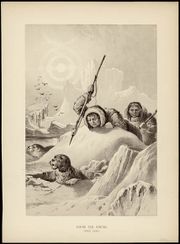

Traditional Inuit hunt

Archeological evidence indicates that the Native Americans and First Nations People in Canada have been hunting seals for at least 4,000 years. Traditionally, when an Inuit boy killed his first seal or caribou, a feast was held. The meat was an important source of fat, protein, vitamin A, vitamin B12 and iron,[11] and the pelts were prized for their warmth. The Inuit diet is rich in fish, whale, and seal.

The Inuit seal hunting accounts for three percent of the total hunt. The traditional Inuit seal hunting is excluded from The European Commission's call in 2006 for a ban on the import, export and sale of all harp and hooded seal products.[12] The natsiq (ringed seal) have been the main staple for food, and have been used for clothing, boots, fuel for lamps, a delicacy, containers, igloo windows, and furnished harnesses for huskies. The natsiq is no longer used to this extent, but ringed seal is still an important food source for the people of Nunavut.[13] Called nayiq by the Central Alaskan Yup'ik people, the ringed seal is also hunted and eaten in Alaska.

History of hunting elsewhere

Seal coats have long been prized for their warmth. Seal oil was often used as lamp fuel, lubricating and cooking oil, for processing such materials as leather and jute, as a constituent of soap, and as the liquid base for red ochre paint.

There is evidence that seals were hunted in northwest Europe and the Baltic Sea more than 10,000 years ago. The first commercial hunting of seals is said to have occurred in 1515, when a cargo of fur seal skins from Uruguay was sent to Spain for sale in the markets of Seville.[14] Sealing became more prevalent in the late 1700s when seal herds in the southern hemisphere began to be hunted by whalers. In 1778, English sealers brought back from the Island of South Georgia and the Magellan Strait area as many as 40,000 seal skins and 2,800 tons of elephant seal oil. In 1791, 102 vessels, manned by 3000 sealers, were hunting seals south of the equator. The principal American sealing ports were Stonington and New Haven, Connecticut.[15] Most of the pelts taken during these expeditions would be sold in China.[14]

The Newfoundland seal hunt became an annually recorded event starting in 1723. By the late 1800s, sealing had become the second most important industry in Newfoundland, second only to cod fishing.[16] In 2007 the commercial seal hunt dividend contributed about $6 million to the Newfoundland GDP, a fraction of the industry's former importance.[17]

Commercial sealing in Australasia appears to have started with Eber Bunker, master of the William and Ann who announced his intention in November 1791 to visit Dusky Sound in New Zealand, did call in that country and had skins on board when he got back to Britain.[18] Captain Raven of the Britannia stationed a party at Dusky from 1792–93 but the discovery of Bass Strait, between mainland Australia and Van Diemen's Land, now called Tasmania, saw the sealers' focus shift there in 1798 when a gang including Daniel Cooper was landed from the Nautilus on Cape Barren Island.[19] With Bass Strait over-exploited by 1802 attention returned to southern New Zealand where Stewart Island/Rakiura and Foveaux Strait were explored, exploited and charted from 1803 to 1804.[20] Thereafter attention shifted to the subantarctic Antipodes Islands, 1805–7, the Auckland Islands from 1806, the south east coast of New Zealand's South Island, Otago Harbour and Solander Island by 1809, before focusing further to the south at the newly discovered Campbell Island and Macquarie Island from 1810.[21] In this time sealers were active on the southern coast of mainland Australia, for example at Kangaroo Island.[22] This whole development has been called the first sealing boom and sparked the Sealers' War in southern New Zealand. By the mid teens of the 19th century, sealing had faded. There was a brief revival from 1823 but this was very short-lived.[23] Although highly profitable at times and affording New South Wales one of its earliest trade staples, its unregulated character saw its self-destruction. Some traders were Australian-based, notably Simeon Lord, Henry Kable, James Underwood and Robert Campbell, but American and British traders and seamen were engaged in it too, such as the Plummers of London and the Whitneys of New York.[24]

By 1830, most seal stocks had been seriously depleted, and Lloyd's records only showed one full-time sealing vessel on its books.[25] Since then, a number of nations have outlawed the hunting of seals and other marine mammals. The landmark North Pacific Fur Seal Convention of 1911 was the first international treaty specifically addressing wildlife conservation.[26] Today, commercial sealing is conducted by only five nations: Canada, Greenland, Namibia, Norway, and Russia. The United States, which had been heavily involved in the sealing industry, now maintains a complete ban on the commercial hunting of marine mammals, with the exception of indigenous peoples who are allowed to hunt a small number of seals each year.[27]

Equipment and method

In regards to the Canadian commercial seal hunt, the majority of the hunters initiate the kill using a firearm. Reportedly, in one case, three out of eight times, the animal was not rendered either dead or unconscious by shooting, and the hunters will then kill the seal using a hakapik or other club of a type that is sanctioned by the governing authority.[28] 90% of sealers on the ice floes of the Front (east of Newfoundland), where the majority of the hunt occurs, use firearms.[29] Canadian sealing regulations describe the dimensions of the clubs and the hakapiks, and caliber of the rifles and minimum bullet velocity, that can be used. They state that: "Every person who strikes a seal with a club or hakapik shall strike the seal on the forehead until its skull has been crushed," and that "No person shall commence to skin or bleed a seal until the seal is dead," which occurs when it "has a glassy-eyed, staring appearance and exhibits no blinking reflex when its eye is touched while it is in a relaxed condition."[30]

Hakapiks

One method of killing seals is with the hakapik: a heavy wooden club with a hammer head and metal hook on the end. The hakapik is used because of its efficiency; the animal can be killed quickly without damage to its pelt. The hammer head is used to crush the skull, while the hook is used to move the carcass.

Modern sealing

Products made from seals

Seal skins have been used by aboriginal people for millennia to make waterproof jackets and boots, and seal fur to make fur coats. Pelts account for over half the processed value of a seal, selling at over C$100 each as of 2006.[31] According to Paul Christian Rieber, of GC Rieber AS, the difficult ice conditions and low quotas in 2006 resulted in less access to seal pelts, which caused the commodity price to be pushed up.[32] One high-end fashion designer, Donatella Versace, has begun to use seal pelts, while others, such as Calvin Klein, Stella McCartney, Tommy Hilfiger, and Ralph Lauren, refrain from using any kind of fur.[33][34]

Seal meat is an important source of food for residents of small coastal communities.[35] Meat is sold to the Asian pet food market; in 2004, only Taiwan and South Korea purchased seal meat from Canada.[36] The seal blubber is used to make seal oil, which is marketed as a fish oil supplement. In 2001, two percent of Canada's raw seal oil was processed and sold in Canadian health stores.[37] There has been virtually no market for seal organs since 1998.[35]

Sealing states

In 2005, three companies exported seal skin: Rieber in Norway, Atlantic Marine in Canada and Great Greenland in Greenland.[38] Their clients were earlier French fashion houses and fur makers in Europe, but today the fur is mainly exported to Russia and China.[38]

Canada

In Canada, the season for the commercial hunt of harp seal is from November 15 to May 15.[39] Most sealing occurs in late March in the Gulf of St. Lawrence, and during the first or second week of April off Newfoundland, in an area known as "The Front." This peak spring period is generally what is referred to as the "Canadian Seal Hunt".[40]

In 2003, the three-year harp seal quota granted by the Department of Fisheries and Oceans was increased to a maximum of 975,000 animals per three years, with a maximum of 350,000 animals in any two consecutive years.[39] In 2006, 325,000 harp seals, as well as 10,000 hooded seals and 10,400 grey seals were killed. An additional 10,000 animals were allocated for hunting by Aboriginal peoples. The current Northwest Atlantic harp seal population is estimated at 5.6 million animals.[41] The seals are killed in two ways: they are either shot or struck on the head with a hakapik, is a spiked club.[41]

Although around 70 percent of Canadian seals killed are killed on "The Front,"[40] private monitors focus on the St. Lawrence hunt, because of its more convenient location.[42] The 2006 St. Lawrence leg of the hunt was officially closed on Apr. 3, 2006. Sealers had exceeded the quota by 1,000 animals by the time the hunt was closed.[43] On March 26, 2007 the Newfoundland and Labrador government launched a seal hunt website.

Warm winters in the Gulf of St. Lawrence have led to thinner and more unstable ice there. In 2007, Canada's federal fisheries ministry reported that while the pups are born on the ice as usual, the ice floes have started to break up before the pups learn to swim, causing the pups to drown.[44] Canada reduced the 2007 quota by 20%, because overflights showed large numbers of seal pups were lost to thin and melting ice.[45] However in southern Labrador and off Newfoundland's northeast coast, there was extra heavy ice in 2007, and the coast guard estimated that as many as 100 vessels were trapped in ice simultaneously.[46][47]

The 2010 hunt was cut short because demand for seal pelts was down. Only one local pelt buyer, NuTan Furs, offered to purchase pelts; and it committed to purchase less than 15,000 pelts.[48] Pelt prices were about $21/pelt in 2010, which is about twice the 2009 price and about 64% of the 2007 price. The reduced demand is attributable mainly to the 2009 ban on imports of seal products into the European Union.

The 2010 winter was unusually warm, with little ice forming in the Gulf of St. Lawrence in February and March, when harp seals give birth to their pups on ice floes. Around the Gulf, harp seals arrived in late winter to give birth on near-shore ice and even on beaches rather than on their usual whelping grounds: sturdy sea ice. Also, seal pups born elsewhere began floating to shore on small, shrinking pieces of ice. Many others stayed too far north, out of reach of all but the most determined hunters. Environment Canada, the weather forecasting agency, reported that the ice was at the lowest level on record.[49]

- Regulations

The Fisheries Act established "Seal Protection Regulations" in the mid-1960s. The regulations were combined with other Canadian marine mammals regulations in 1993, to form the "Marine Mammal Regulations".[50][51][52] In addition to describing the use of the rifle and hakapik , the regulations state that every person "who fishes for seals for personal or commercial use shall land the pelt or the carcass of the seal."[42] The commercial hunting of infant harp seals (whitecoats) and infant hooded seals (bluebacks) was banned in 1987 under pressure from animal rights groups. Now seals may only be killed once they have started molting (from 12 to 15 days of age) as this coincides with the time when they are abandoned by their mothers.

- Export

Canada's biggest market for seal pelts is Norway.[53] Carino Limited is one of Newfoundland's largest seal pelt producers. Carino (CAnada–RIeber–NOrway) is marketing its seal pelts mainly through its parent company, GC Rieber Skinn, Bergen, Norway.[54] Canada sold pelts to eleven countries in 2004. The next largest were Germany, Greenland, and China/Hong Kong. Other importers were Finland, Denmark, France, Greece, South Korea, and Russia.[55] Asia remains the principal market for seal meat exports.[56] One of Canada's market access priorities for 2002 was to "continue to press Korean authorities to obtain the necessary approvals for the sale of seal meat for human consumption in Korea."[57] Canadian and Korean officials agreed in 2003 on specific Korean import requirements for seal meat.[58] For 2004, only Taiwan and South Korea purchased seal meat from Canada.[36]

Canadian seal product exports reached $18 million (CAD) in 2006. Of this, $5.4 million went to the EU.[59] In 2009 the European Union banned all seal imports, shrinking the market.[60] Where pelts once sold for more than $100, they now fetch $8 to $15 each.[49]

Greenland

Although official figures for the Greenland seal hunt are not available, the government of Canada estimates that 20,000 to 25,000 seals are killed in Greenland annually.[61] In January 2006, the government of Greenland banned imports of Canadian seal skins, citing fears that Canadian seals are brutally beaten to death. The boycott may be an effort to distance Greenland's own seal hunt from Canada's, and spare themselves negative press in the process.[62] The ban was rescinded in May 2006, with the Greenland Home Rule Government noting that the seal hunt in Canada has sensible regulations on hunting methods, drawn up in close cooperation with biologists, veterinarians, weapons experts and seal hunters. It further noted that seal-hunting in Canada is subject to strict and extensive control measures, to ensure the use of effective and humane killing methods.

In Greenland seal hunting is conducted with rifles - the seals being shot in the head from a small open boat while they sit on an ice flow. The shot needs to be very accurate and the boat must rush up to the seal to hook the carcass out of the water where it falls within a few seconds before it sinks. The economy of certain very rural Greenlandic villages such as Aappilattoq are highly dependent upon such seal hunting.[63]

Namibia

| Year | Annual Quota | Catch |

| Before 1990 | 17,000 pups[64] | |

| 1998–2000 | 30,000 pups[65] | |

| 2001–2003 | 60,000 pups[65] | |

| 2004–2006 | 60,000 pups, 7,000 bulls[65] | |

| 2007 | 80,000 pups, 6,000 bulls[66] | |

| 2008 | 80,000 pups, 6,000 bulls[66] | 23,000 seals[67] |

| 2009 | 85,000 pups, 7,000 bulls[68] | |

| 2010 | 85,000 pups, 7,000 bulls[68] |

Namibia is the only country in the southern hemisphere culling seals. Although the protection and the sustainable use of natural resources is part of Namibia's constitution it regularly conducts the second highest seal harvest in the world,[65] mainly because of the huge amount of fish seals are estimated to consume. While a government-initiated study found that seal colonies consume more fish than the entire fishing industry can catch,[66] animal protection society Seal Alert South Africa estimated only less than 0,3 per cent losses to commercial fisheries.[64]

Harvesting is done from July to November[64] on two places, Cape Cross and Atlas Bay, in the past also at Wolf Bay.[66] These two colonies together account for 75% of the Cape fur seal population of the country.[65]

Cape Cross is a tourism resort and the largest Cape fur colony in Namibia. In season, the resort is closed and sealed off during the culling in the early morning hours, journalists are not allowed to enter.[67] Namibia’s Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (SPCA) is allowed to observe the culling from 2010 onwards.[68]

Namibia's Ministry of Fisheries announces a three-year rolling quota for the seal harvest, although different quotas per year are sometimes reported.[66][67] The latest[update] quota announced was in 2009, valid until 2011.[68] The quotas are usually not filled by the concession holders.[64]

In 2009 an unusual bid to end seal culling in Namibia was attempted when Seal Alert tried to raise money to purchase the only buyer of Namibian seals, Australian-based Hatem Yavuz, lock, stock, and barrel for US$14,2 million.[67] The project did not materialise. The Government of Namibia on the other hand offered the International Fund for Animal Welfare (IFAW) an opportunity to buy out the two sealers in Namibia to finally end the culling. The offer was rejected.[65]

Norway

| Year | Quota | Catch |

| 1950 | 255,056[69] | |

| 1955 | 295,172[69] | |

| 1960 | 216,034[69] | |

| 1965 | 140,118[69] | |

| 1970 | 188,980[69] | |

| 1975 | 112,274[69] | |

| 1980 | 60,746[69] | |

| 1985 | 19,902[69] | |

| 1990 | 15,232[69] | |

| 1992 | 14,076[70] | |

| 1993 | 12,772 | |

| 1994 | 18,113 | |

| 1995 | 15,981 | |

| 1996 | 16,737 | |

| 1997 | 10,114 | |

| 1998 | 9,067 | |

| 1999 | 6,399 | |

| 2000 | 20,549 | |

| 2001 | ||

| 2002 | 10,691[71] | |

| 2003 | 12,870[69] | |

| 2004 | 30,600[72] | 14,746[69] |

| 2005 | 30,600 [73] | 21,597[69] |

| 2006 | 45,200 [74] | 17,037[69] |

| 2007 | 46,200 [75] | 8,000[76] |

| 2008 | 31,000 [76] | 1,260[77] |

The Norwegian sealing season runs from January to September. The hunt involves seal catching by seagoing sealing boats on the Arctic ice shelf, and seal hunting on the coast and islands of mainland Norway. The latter is carried out by small groups of licenced hunters shooting seals from land and using small boats to retrieve the catch.

In 2005, Norway began offering seal hunting as a tourist attraction.[78] In 2006, 17,037 seals (including 13,390 harp and 3,647 hooded seals) were harvested.[79] In 2007 the Norwegian Ministry of Fisheries and Coastal Affairs stated that up to 13.5 million Norwegian krone (ca 2.6 mill. US dollar) would be given in funding, to vessels in the 2007 Norwegian seal hunt.[80]

Regulations

All Norwegian sealing vessels are required to carry a qualified veterinary inspector on board.[81] Norwegian sealers are required to pass a shooting test each year before the season starts, using the same weapon and ammunition as they would on the ice. Likewise they have to pass a hakapik test.[82]

Adult seals that are more than one year old must be shot in the head with expanding bullets, and can not be clubbed to death. The hakapik shall be used to ensure that the animal is dead. This is done by crushing the skull of the shot adult seal with the short end of the hakapik, before the long spike is thrust deep into the animal's brain. The seal shall then be bled by making an incision from its jaw to the end of its sternum. The killing and bleeding must be done on the ice, and live animals may never be brought onboard the ship. Young seals may be killed using just the hakapik, but only in the before mentioned manner, i.e. they need not be shot.[82]

Seals that are in the water and seals with young may not be killed, and the use of traps, artificial lighting, aeroplanes or helicopters is forbidden.[82]

The hakapik may only be used by certified seal-catchers (fangstmenn) operating in the pack ice of the Arctic Ocean and not by coastal seal-hunters. All coastal seal-hunters must be pre-approved by the Norwegian Directorate of Fisheries and have to pass a large game hunting test.[83]

In 2007 the European Food Safety Agency confirmed that the animals are put to death faster and more humanely in the Norwegian sealing than in large game hunting on land.[81]

Export

In Norway in 2004, only Rieber worked with sealskin and seal oil.[84] In 2001, the biggest producer of raw seal oil, was Canada. (Two percent of the raw oil was processed and sold in Canadian health stores.[37]) Rieber had the majority of all distribution of raw seal oil in the world market, but there was no demand for seal oil.[37] From 1995 to 2005 Rieber annually received between 2 and 3 million Norwegian krone in subsidy.[85] In a 2003–2004 parliamentary report, it says that CG Rieber Skinn is the only company in the world that delivers skin from bluebacks.[86] Most of the skins processed by Rieber, have been imported from abroad, mainly from Canada. Only a small portion is from the Norwegian hunt. Of the processed skin, 5 percent is sold in Norway, the rest is exported to the Russian and Asian market.[32]

Fortuna Oils AS (established in 2004) is a 100% owned subsidiary of GC Rieber.[87] They get the majority of their raw oil imported from Canada.[88] They also have access to raw oil from the Norwegian hunt.[88]

Russia

The Russian seal hunt has not been well monitored since the break-up of the Soviet Union.[89] The quota in 1998 was 35,000 animals.[90] There have been reports that many whitecoat pups are not properly killed and are transported, while injured, to processing areas. In January 2000, a bill to ban seal hunting was passed by the Russian parliament by 273 votes to 1, but was vetoed by President Vladimir Putin.[91]

On September 21, 2007 in Arhangelsk, the Norwegian company GC Rieber Skinn AS, proposed a joint Russian–Norwegian seal hunting project. The campaign was carried out from one hunt boat supplied by GS Rieber skinn AS in 2007, lasted 2 weeks and brought in 40 000 roubles per Russian hunter. GS Rieber skinn AS declared a plan to order 20 boats and donate them to the Pomor.[92] CG Rieber Skinn AS, in 2007 established a daughter company in Arkhangelsk, called GC Rieber Skinn Pomor'e Lic. (GC Rieber Skinn Pomorje).

The Norwegian company Polardrift AS, in 2007, had plans to establish a company in Russia, and operate under Russian flag, in close cooperation with GC Rieber Skinn Pomor'e.

Plans for the 2008 season included both helicopter-based hunt, mainly to take whitecoats, and boat-based hunt, mainly targeting beaters.[93]

On March 18, 2009, Russia's Minister of Natural Resources and Ecology, Yuriy Trutnev, announced a complete ban on the hunting of harp seals younger than one year of age in the White Sea.[94]

Sealing debate

Canada has become the center of the sealing debate because of the comparatively large size of its hunt.

Cruelty to animals

Any discussion of potential cruelty to animals needs to be placed in the context of their natural behavior, habitat and life events. A large number of seal pups move approach the ice edge before they are ready to swim and drown. The number of pups that drown is estimated at at least twice to three times the number of pups allowed taken by the Canadian authorities.

According to recent studies done by the Canadian Veterinary Medical Association (CVMA), the hakapik, when used properly, kills the animal quickly and painlessly. However, the aforementioned CVMA report also urges "continued attention to this hunt" due to nine types of "violations and abuses."[42] The Royal Commission on Seals and the Sealing Industry in Canada, also known as the Malouf Commission, claims that properly performed clubbing is at least as humane as the methods used in commercial slaughterhouses, and according to the Department of Fisheries and Oceans Canada (DFO), these studies "have consistently proven that the club or hakapik is an efficient tool designed to kill the animal quickly and humanely." Another study, conducted by the IFAW, an anti-sealing group, disputes these findings, however, detailing that in 42% of cases there was not enough evidence of cranial injury to guarantee unconsciousness at the time of skinning, and in 79% of cases sealers did not check to ensure that the seals were dead prior to skinning them.[95]

A study of the 2001 Canadian seal hunt conducted by five independent veterinarians, commissioned by the International Fund for Animal Welfare (IFAW),[96] concluded that, although the hakapik is a humane means of hunting, many hunters were not using it properly. This improper use, they said, was leading to "considerable and unacceptable suffering," and in 17 percent of the cases they observed, there were no detectable lesions of the skull whatsoever. In numerous other cases, the seals had to be struck multiple times before they were considered "unconscious." These findings are at odds with the CVMA report which states that Daoust, at the same time and in the same location, recorded that 86 percent of skulls had been completely crushed by strikes with hakapiks. It states further that two years previously, Bollinger and Campbell had recorded that 98.2 percent of the skulls examined were completely crushed.[97] The IFAW is an organization founded for purpose of opposing the Canadian seal hunt and their 2002 study was not peer reviewed.

In 2005, the World Wildlife Fund (WWF) commissioned the Independent Veterinarians Working Group Report. With reference to video evidence, the report states: "Perception of the seal hunt seems to be based largely on emotion, and on visual images that are often difficult even for experienced observers to interpret with certainty. While a hakapik strike on the skull of a seal appears brutal, it is humane if it achieves rapid, irreversible loss of consciousness leading to death."[98]

The 2001 report contained a number of recommendations on how sealing could be conducted more humanely. They did not, however, recommend the disuse of the hakapik. Actually, the report recommended more training, mandatory blink-reflex tests for unconsciousness, and the cessation of open-water hunting. The report also recommended that seals be bled out immediately after clubbing, in order to ensure that the animals are unconscious when skinning begins. This is a recommendation taken in response to incidents of seals regaining consciousness after clubbing.[99] It has also been strongly recommended that seals killed by guns to be shot to a quick death, not be wounded and left to die. The 2002 CVMA report, however, indicated an average time of 45.2 seconds between the animal being shot and a sealer killing it with a hakapik. The report concluded that this time compared well with established and acceptable humane killing practices according to the Agreement on International Humane Trapping Standards where acceptable times range from 45 to 300 seconds.

Ecological feasibility

According to the DFO, the harp seal population is now stable at about five million animals, three times as many seals as in the 1970s. They say that Canada's annual quota of 325,000 harp seals, and an additional 10,000 harp seal allowance for new Aboriginal initiatives, personal use, and Arctic hunts, does not significantly impact the harp seal population. Protestors respond that this figure represents only a fraction of the total number of seals killed, because many seals' bodies fall into the water or under the ice and are not counted. The CVMA has replied that this is untrue for the Canadian seal hunt, and that the Canadian seals that have been "struck and lost" is less than five percent (16,250 animals) of the total harvest. They suggest that this is because, in Canada, the majority of seals are killed on the ice, not in the sea.[100]

Greenpeace has further stated that the quota is an unreliable estimate of the total kill, not only because of "struck and lost" statistics, but also because seals with pelt damage are discarded and not accounted for.[101]

Objections to fur

Animal welfare advocates and organizations such as PETA, object to the use of real fur when many synthetic "faux fur" alternatives are available. Fur advocates claim that faux fur does not compare to real fur's superior warmth and style. They also claim that it is a renewable resource and synthetic fur is a petroleum based product and can release highly toxic prussic acid into the environment.[102]

Economic impact

According to Canadian authorities, the value of the 2004 seal harvest was $16.5 million CAD, which significantly contributes to seal manufacturing companies, and for several thousand fishermen and First Nations peoples. For some sealers, they claim, proceeds from the hunt make up a third of their annual income. Critics, however, say that this represents only a tiny fraction of the $600-million Newfoundland fishing industry. Sealing opponents also say that $16.5 million is insignificant, compared to the funding required to regulate and subsidize the hunt. For 1995 and 1996 there are confirmed reports that The Department of Fisheries and Oceans encouraged maximum utilization of harvested seals through a $0.20 per pound meat subsidy.[103] The level of subsidy totalled $650,000 in 1997, $440,000 in 1998 and $250,000 in 1999. There were no meat subsidies in 2000.[104] Some critics, such as the McCartneys (see below), have suggested that promoting that area as an eco-tourism site would be far more lucrative than the annual harvest.[105]

As a culling method

In March 2005, Greenpeace asked the DFO to "dispel the myth that seals are hampering the recovery of cod stocks." In doing so, they implied that the seal hunt is, at least in part, a cull designed to increase cod stocks. Cod fishing has traditionally been a key part of the Atlantic fishery, and an important part of the economy of Newfoundland and Labrador. The Department of Fisheries and Oceans have responded that there is no connection between the annual seal harvest and the cod fishery, and that the seal hunt is "established on sound conservation principles."[106]

Protests

Many animal-protection groups encourage people to petition against the harvest. Respect for Animals and Humane Society International believe the hunt will be ended only by the financial pressure of a boycott of Canadian seafood. In 2005, the Humane Society of the United States (HSUS) called for such a boycott in the United States.[107]

Protesters frequently use images of whitecoats, despite Canada's ban on the commercial hunting of suckling pups. The HSUS explains this by saying that images of the legally hunted "ragged jackets" are nearly indistinguishable from those of whitecoats. Also, they state that according to official DFO kill reports, 97% percent of the estimated million harp seals killed in the last four years have been under three months old, and the majority of these are less than one month old.[108] [109]

On March 26, 2006, seven protesters were arrested in the Gulf of St. Lawrence for violating the terms of their observer permits. By law, observers must maintain a ten-meter distance between themselves and the sealers.[110] In the same month, as part of a counter-protest, Newfoundland and Labrador Premier Danny Williams encouraged people in the province to boycott Costco after the retailer decided to stop carrying seal-oil capsules.[111] Costco stated that politics played no role in their decision to remove the capsules, and on April 4 that year, they were again being sold in Costco stores.[112]

The law was approved by the Council of the European Union without debate on July 27, 2009.[113] Denmark, Romania, and Austria abstained.[114] The Canadian government responded to the move by stating that it will take the European Union to the World Trade Organization if the ban does not exempt Canada.[115] Canadian Inuits from Nunavut territory have opposed the ban and lobbied European Parliament members against it.[116] The legislation banning seal products is likely to come into effect before the beginning of the hunting season in 2010.[116]

Celebrity involvement

Numerous celebrities have opposed the commercial seal hunt. Rex Murphy has reported that celebrities have been used by anti-hunt activists since the mid-20th century; Yvette Mimieux and Loretta Swit were recruited to attract the attention of international gossip magazines.[117] Other celebrities who've aligned themselves against the hunt include Richard Dean Anderson, Kim Basinger, Juliette Binoche,[118] Sir Paul McCartney, Heather Mills, Pamela Anderson, Martin Sheen, Pierce Brosnan, Paris Hilton, Robert Kennedy, Jr.,[119] Rutger Hauer,[120] Brigitte Bardot, Ed Begley, Jr., Farley Mowat, Linda Blair, the Red Hot Chili Peppers,[121] Jet, The Vines, Pink, The Darkness, Good Charlotte, and Animal Collective.[122]

In March 2006, Brigitte Bardot traveled to Ottawa to protest the hunt, though the prime minister turned down her request for a meeting. During the same month, Paul McCartney and Heather Mills McCartney toured the Gulf of St. Lawrence's sealing grounds, and spoke out against the seal hunt, including as guests on Larry King Live, where the two debated with Danny Williams, the Premier of Newfoundland and Labrador.

In 1978, Marine ecologist Jacques Cousteau criticized the focus on the seal hunt, arguing that it is entirely emotional. "We have to be logical. We have to aim our activity first to the endangered species. Those who are moved by the plight of the harp seal could also be moved by the plight of the pig - the way they are slaughtered is horrible."[123]

In fiction

- Kipling's The White Seal, part of The Jungle Book, describes seal hunting from the seals' point of view, with the central character being a white seal seeking for his seals a safe haven from hunters.

- Jack London's novel The Sea Wolf takes place aboard "the schooner Ghost, bound seal-hunting for Japan" circa 1893.

- In the web-based MMORPG Kingdom of Loathing, one of the classes available for selection is a Seal Clubber.

See also

- Animal welfare

- John Davis (sealer)

- Flipper pie

- Odd F. Lindberg

- Seal finger

- Jerry Vlasak

- Whaling

References

- ↑ Seal hunt set to resume off Newfoundland's coast, CTV.ca, April 12, 2006

- ↑ Stock Assessment of Northwest Atlantic Harp Seals

- ↑ "Harp Seal", Marine Animal Response Society.

- ↑ Norwegian Fishing Authority.

- ↑ Minister Hearn Announces 2007 Management Measures for Atlantic Seal Hunt

- ↑ M.O. Hammill & G. Stenson, abundance of Northwest Atlantic harp seals (1960–2005) (2005)

- ↑ "EFSA Animal Welfare aspects of the killing and skinning of seals - Scientific Opinion of the Panel on Animal Health and Welfare". Efsa.europa.eu. http://www.efsa.europa.eu/EFSA/efsa_locale-1178620753812_1178671319178.htm. Retrieved 2009-05-07.

- ↑ "Myths and Facts: The Truth about Canada's Commercial Seal Hunt". hsicanada.ca. http://www.hsicanada.ca/wildlife/seals/seal_myths_and_facts.html. Retrieved 2009-05-26.

- ↑ ""Activists Decry Growth Of Canadian Seal Hunt"". washingtonpost.com. http://www.washingtonpost.com/ac2/wp-dyn/A20625-2004Apr17?language=printer. Retrieved 2009-05-26.

- ↑ "Harp seal: The sealing industry," Encyclopaedia Britannica, 2008.

- ↑ "Nutritional composition of blubber and meat of hooded seal and harp seal"

- ↑ "Euro MPs call for ban on seal products — EUbusiness.com - business, legal and economic news and information from the European Union". Eubusiness.com. 2006-09-07. http://www.eubusiness.com/Environ/060906222345.cyu8d8wj. Retrieved 2009-05-07.

- ↑ "Eskimo Art, Inuit Art, Canadian Native Artwork, Canadian Aboriginal Artwork". Inuitarteskimoart.com. http://inuitarteskimoart.com/artists/About-Seals.html. Retrieved 2009-05-07.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 "History of World Fur Sealing".

- ↑ Muir, Diana, Reflections in Bullough's Pond, University Press of New England, 2001

- ↑ "Canadian Geographic Sealing Timeline". http://www.canadiangeographic.ca/Magazine/JF00/sealtimeline.asp.

- ↑ Newfoundland and Labrador

- ↑ Peter Entwisle, Behold the Moon: The European Occupation of the Dunedin District 1770-1848, Dunedin, NZ: Port Daniel Press, 1998, pp.10–11.

- ↑ Robert McNab, Murihiku, Invercargill, NZ: 1907, pp.70–71 & 78–79.

- ↑ Entwisle, 1998, pp.13–15.

- ↑ Entwisle, 1998, pp.13–16; Ian S. Kerr, Campbell Island a History Wellington, NZ: A.H. & A. W. Reed, 1976; J.S. Cumpston, Macquarie Island, Canberra, Aus: Antarctic Division, Department of External Affairs, 1968.

- ↑ J.S. Cumpston, Kangaroo Island, Canberra, Aus: Roebuck Society, 1970.

- ↑ McNab, 1907.

- ↑ Entwisle, 1998; Edmund Fanning, Voyages Round the World..., New York, US: Collins & Hannay, 1833; D.R. Hainsworth, The Sydney Traders, Simeon Lord and his Contemporaries 1788-1821, Melbourne, Sydney, Aus: Cassell Australia, 1971; Margaret Steven, Merchant Campbell 1769-1846 a Study in the Colonial Trade, Melbourne, Aus: Oxford University Press, 1965.

- ↑ "History of World Fur Sealing". http://www.fahan.tas.edu.au/macquarie_island/infohut/sealing.htm.

- ↑ "North Pacific Fur Seal Treaty of 1911". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. http://celebrating200years.noaa.gov/events/fursealtreaty/welcome.html#treaty.

- ↑ "Commentary & Editorials", Sea Shepherd Conservation Society, 2003.

- ↑ "Animal Welfare aspects of the killing and skinning of seals - Scientific Opinion of the Panel on Animal Health and Welfare". European Food Safety Authority. Published: 19 December 2007. http://www.efsa.europa.eu/EFSA/efsa_locale-1178620753812_1178671319178.htm. Retrieved 20 August 2010.

- ↑ "Animal Welfare in Canada". http://www.sealsandsealing.net/welfare.php?page=3&id=1.

- ↑ "Marine Mammal Regulations, SOR/93-56". Canlii.org. http://www.canlii.org/ca/regu/sor93-56/. Retrieved 2009-05-07.

- ↑ "Seal pelts fetch record prices". Cbc.ca. 2006-04-19. http://www.cbc.ca/canada/newfoundland-labrador/story/2006/04/19/nf-seal-pelt-20060419.html. Retrieved 2009-05-07.

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 Kjøligere for Rieber Skinn (Norwegian), Bergens Tidende, September 12, 2007

- ↑ Save Canadian Seals List of Seal Pelt Users.

- ↑ Independent Online. "(Fur)shion show without clothes". Iol.co.za. http://www.iol.co.za/index.php?from=rss_News&set_id=1&click_id=79&art_id=nw20071002160158869C509823. Retrieved 2009-05-07.

- ↑ 35.0 35.1 "Canadian seal hunt attacked by peta". http://theportcitypost.com/2009/06/11/canadian-seal-hunt-attacked-by-peta/.

- ↑ 36.0 36.1 "Seal Hunt Facts". http://www.seashepherd.org/seals/seals_seal_hunt_facts.html.

- ↑ 37.0 37.1 37.2 5 Forslag til tiltak (Norwegian), Government of Norway, March, 2001

- ↑ 38.0 38.1 Sel skinn selger igjen (Norwegian), Aftenposten, May 2, 2005. Retrieved on 2008-05-06

- ↑ 39.0 39.1 "Atlantic Seal Hunt 2003-2005 Management Plan", Fisheries and Aquaculture Management, Canada.

- ↑ 40.0 40.1 "Frequently Asked Questions About Canada's Seal Hunt", Fisheries and Aquaculture Management, Canada.

- ↑ 41.0 41.1 Sturcke, James (2010-03-08). "Canadian MPs put seal meat on parliament's menu in rebuff to EU". The Guardian (London). http://www.guardian.co.uk/world/2010/mar/08/sealmeat-canada-ottawa. Retrieved 2010-05-23.

- ↑ 42.0 42.1 42.2 Daoust PY, Crook A, Bollinger TK, Campbell KG, Wong J (September 2002). "Animal welfare and the harp seal hunt in Atlantic Canada". Can. Vet. J. 43 (9): 687–94. PMID 12240525.

- ↑ "Seal hunt haul 1,000 over quota". CBC News. April 2006. http://www.cbc.ca/canada/story/2006/04/03/seal-quota060403.html.

- ↑ 4:22 p.m. ET (2007-03-27). "Seal hunt might be on ice due to lack of it". MSNBC. http://www.msnbc.msn.com/id/17736236/. Retrieved 2009-05-07.

- ↑ Struck, Doug (2007-04-04). "Warming Thins Herd for Canada's Seal Hunt". Washington Post. http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2007/04/03/AR2007040301754.html. Retrieved 2008-02-18.

- ↑ "Heavy ice keeps dozens of vessels from seal hunt". Cbc.ca. 2007-04-13. http://www.cbc.ca/canada/newfoundland-labrador/story/2007/04/13/seals-ice.html. Retrieved 2009-05-07.

- ↑ "Canadian seal hunters could remain trapped by ice for a week: coast guard". International Herald Tribune. 2009-03-29. http://www.iht.com/articles/ap/2007/04/19/america/NA-GEN-Canada-Seal-Hunt-Evacuation.php. Retrieved 2009-05-07.

- ↑ 4:03 p.m. ET (2010-04-15). "Canada's seal hunt to close early after low harvest". AFP. http://news.yahoo.com/s/afp/20100415/sc_afp/canadahuntinganimaleu. Retrieved 2010-05-02.

- ↑ 49.0 49.1 Austen, Ian (April 1, 2010). "Despite Few Hunters, Seal Pups Face Threats". New York Times.

- ↑ Sealing Industry, Government of Newfoundland and Labrador

- ↑ Improvements to Seal Hunt Management Measures, Fisheries and Oceans Canada

- ↑ Sealing, The Canadian Encyclopedia

- ↑ "EU politicians push to ban Canadian seal product imports". CBC News. 2006-09-06. http://www.cbc.ca/world/story/2006/09/06/seal-hunt-eu.html. Retrieved 2007-10-24.

- ↑ "Secondary Processing of Seal Skins". http://66.249.93.104/search?q=cache:Z6XwFFBUxGQJ:www.fishaq.gov.nl.ca/fdp/ProjectReports/fdp_248.pdf+seal+pelts+norway&hl=en&ct=clnk&cd=1.

- ↑ "Seal Hunt Facts". Sea Shepherd Conservation Society. http://www.seashepherd.org/seals/seals_seal_hunt_facts.html.

- ↑ "Seals and sealing in canada". http://www.dfo-mpo.gc.ca/seal-phoque/reports-rapports/mgtplan-plangest2003/mgtplan-plangest2003_e.htm.

- ↑ "?". http://www.sice.oas.org/geograph/mktacc/canada.pdf.

- ↑ "Canada's International Market Access Priorities". 2004. http://www.dfait-maeci.gc.ca/tna-nac/2004/pdf/cimap-en.pdf. Retrieved 2007-10-24.

- ↑ "The Institute for European Studies". Ies.ubc.ca. 2008-08-29. http://www.ies.ubc.ca/index.php?option=com_content&task=view&id=152&Itemid=198. Retrieved 2009-05-07.

- ↑ European Parliament (9 November 2009). "MEPs adopt strict conditions for the placing on the market of seal products in the European Union". Hearings. European Parliament. http://www.europarl.europa.eu/sides/getDoc.do?pubRef=-//EP//TEXT+IM-PRESS+20090504IPR54952+0+DOC+XML+V0//EN. Retrieved 12 March 2010.

- ↑ "The Harp Seal". Department of Fisheries and Oceans Canada. http://www.dfo-mpo.gc.ca/zone/underwater_sous-marin/hseal/seal-phoque_e.htm.

- ↑ Greenland bans Canadian sealskins – UPI.com

- ↑ Lonely Planet Greenland & The Arctic 2nd edition, 2005

- ↑ 64.0 64.1 64.2 64.3 "Time for Namibia to see the tourism value of seals". The Namibian. 17 June 2010. http://www.namibian.com.na/news/environment/full-story/archive/2010/june/article/time-for-namibia-to-see-the-tourism-value-of-seals/.

- ↑ 65.0 65.1 65.2 65.3 65.4 65.5 Robberts, Elma (5 June 2006). "Seal culling season sparks new protests". The Namibian. http://www.namibian.com.na/index.php?id=28&tx_ttnews%5Btt_news%5D=25156&no_cache=1.

- ↑ 66.0 66.1 66.2 66.3 66.4 Weidlich, Brigitte (28 June 2007). "Seal quota down for this season". The Namibian. http://www.namibian.com.na/index.php?id=28&tx_ttnews%5Btt_news%5D=36659&no_cache=1.

- ↑ 67.0 67.1 67.2 67.3 Weidlich, Brigitte (30 June 2009). "Million-dollar bid to end seal clubbing". The Namibian. http://www.namibian.com.na/news-articles/national/full-story/archive/2009/june/article/million-dollar-bid-to-end-seal-clubbing.

- ↑ 68.0 68.1 68.2 68.3 Weidlich, Brigitte (10 June 2010). "Seal activists ready to prevent 2010 culling". The Namibian. http://www.namibian.com.na/index.php?id=28&tx_ttnews%5Btt_news%5D=68826&no_cache=1.

- ↑ 69.00 69.01 69.02 69.03 69.04 69.05 69.06 69.07 69.08 69.09 69.10 69.11 69.12 374 Selfangst, Statistisk Sentralbyrå, 2007

- ↑ Strategier og tiltak for å utvikle lønnsomheten i norsk selnæring, Norwegian Ministry of Fisheries and Coastal Affairs, March, 2001

- ↑ Norge må starte storstilt selfangst, Dagbladet, April 17, 2004

- ↑ Forskrift om regulering av fangst av sel i Vesterisen og østisen i 2004, Norwegian Ministry of Fisheries and Coastal Affairs

- ↑ 1 Forskrift om regulering av fangst av sel i Vesterisen og Østisen i 2005, Norwegian Ministry of Fisheries and Coastal Affairs, January 13, 2005

- ↑ Forskrift om endring av forskrift om regulering av fangst av sel i Vesterisen og Østisen i 2006, Norwegian Ministry of Fisheries and Coastal Affairs, March 13, 2006

- ↑ Selfangst – statsfinansiert dyrplageri, Norge IDAG, April 16, 2007

- ↑ 76.0 76.1 Fryktar selinvasjon på kysten, NRK, March 6, 2008

- ↑ Tre av fire blir hjemme (Norwegian), NRK, March 10, 2009

- ↑ "Fact sheet on Norwegian coastal seals - regjeringen.no". Odin.dep.no. http://odin.dep.no/fkd/english/news/news/047041-990012/dok-bn.html. Retrieved 2009-05-07.

- ↑ Statistics Norway: Sealing

- ↑ Selfangsten i 2007 (Norwegian), Government of Norway, February 27, 2007

- ↑ 81.0 81.1 By the Norwegian Ministry of Foreign Affairs (2009-04-03). "Norwegian Sealing". Norway.org. http://www.norway.org/policy/environment/sealing/sealing.htm. Retrieved 2009-05-07.

- ↑ 82.0 82.1 82.2 "Forskrift om utøvelse av selfangst i Vesterisen og Østisen". Lovdata.no. 2003-02-11. http://lovdata.no/for/sf/fi/ti-20030211-0151-0.html#1. Retrieved 2009-05-07.

- ↑ "For 1996-05-06 nr 414: Forskrift om forvaltning av sel på norskekysten". Lovdata.no. http://www.lovdata.no/cgi-wift/ldles?doc=/sf/sf/sf-19960506-0414.html#10. Retrieved 2009-05-07.

- ↑ Utviklingsplan for selspekk (.pdf file) (Norwegian), Fiskeri- og havbruksnæringens forskningsfond (FHF), February, 2004

- ↑ Norge betaler for kanadisk seljakt, VG, March 30, 2005

- ↑ St.meld. nr. 27 (2003-2004) – Norsk sjøpattedyrpolitikk(Norwegian). Government of Norway (2003–2004)

- ↑ News archives – Fortuna Oils AS increases its ownership in OliVita AS, Olivita AS, April 26, 2006

- ↑ 88.0 88.1 Fortuna Oils, Fortuna Oils

- ↑ "SCS: Caspian Seal (Phoca caspica)". Pinnipeds.org. http://www.pinnipeds.org/species/caspian.htm. Retrieved 2009-05-07.

- ↑ "News from the High North Alliance". Highnorth.no. http://www.highnorth.no/news/nedit.asp?which=175. Retrieved 2009-05-07.

- ↑ "Harp Seal, Pagophilus groenlandicus at". Marinebio.org. http://marinebio.org/species.asp?id=302. Retrieved 2009-05-07.

- ↑ Istomina, Ludmila. "Rieber Skinn AS has proposed to the Pomors". The Norwegian Barents Secretariat. http://www.barents.no/rieber-skinn-as-has-proposed-to-the-pomors.538786-43497.html. Retrieved 2008-03-04.

- ↑ "The 36th Session of the Joint Norwegian - Russian Fisheries Commission, St Petersburg, Russia, 22–26 October 2007 (.pdf-file)". Government of Norway. http://www.regjeringen.no/Upload/FKD/Vedlegg/Kvoteavtaler/2008/russland/vedlegg%208%20sel%20notxtsistev.pdf. Retrieved 2008-03-04.

- ↑ Extraordinary Victory for Seals: Russia Bans the Hunt for All Harp Seals Less Than One Year of Age, MSNBC, March 18, 2009

- ↑ Linzey, Andrew (2006). "An Ethical Critique of the Canadian Seal Hunt and an Examination of the Case for Import Controls on Seal Products". The Journal of Animal Law 2: 87–119. http://www.animallaw.info/articles/arus2journalanimallaw87.htm.

- ↑ "Ensuring A Sustainable And Humane Seal Harvest". Cmte.parl.gc.ca. http://cmte.parl.gc.ca/Content/HOC/committee/391/fopo/reports/rp2872843/foporp04/05_report-e.htm. Retrieved 2009-05-07.

- ↑ "Animal welfare and the harp seal hunt in Atlantic Canada". Pubmedcentral.nih.gov. 2002-04-27. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=339547. Retrieved 2009-05-07.

- ↑ Independent Veterinarians Working Group Report.

- ↑ "?". June 2009. http://www.hsus.org/marine_mammals/protect_seals/news_reports_2005_seal_hunt/news_from_the_2005_seal_hunt_march_29.html.

- ↑ "?". http://www.dfo-mpo.gc.ca/media/infomedia/2005/im01_e.htm.

- ↑ "Greenpeace press release".

- ↑ "Soy now comes in Teddy Bear Form". http://www.planetark.com/dailynewsstory.cfm/newsid/35620/story.htm.

- ↑ December 18, 1995; Tobin announces 1996 Atlantic Seal Management Plan; Fisheries and Oceans Canada; retrieved from www.dfo-mpo.gc.ca February 24, 2008.

- ↑ 2000; Seals and Sealing in Canada; Fisheries and Oceans Canada; retrieved from www.dfo-mpo.gc.ca February 24, 2008.

- ↑ "BBC". BBC News. 2006-03-03. http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/entertainment/4769628.stm. Retrieved 2010-01-04.

- ↑ "Canadian Seal Hunt Myths and Realities".

- ↑ "UnderwaterTimes Canadian Seafood Boycott Ends Year With Growing Momentum". Underwatertimes.com. http://www.underwatertimes.com/news.php?article_id=09210631845. Retrieved 2009-05-07.

- ↑ "The Truth The Humane Society of the United States". Hsus.org. http://www.hsus.org/marine_mammals/protect_seals/the_truth.html. Retrieved 2009-05-07.

- ↑ ""Humane Society International: Canada Should Follow Russia’s Lead; Ban Commercial Seal Slaughter"". hsus.org. http://www.hsus.org/hsi/press_room/press_releases/canada_should_follow_russias_ban_on_seal_slaughter_031909.html. Retrieved 2009-05-26.

- ↑ Seven protesters arrested as tempers flare in seal hunt, CBC News.

- ↑ Williams takes aim at Costco over seal-oil fuss, CBC News.

- ↑ CBC.ca - Experiencing Technical Difficulties

- ↑ "Canada to fight EU seal product ban". CBC News. 2009-07-27. http://www.cbc.ca/canada/nova-scotia/story/2009/07/27/seal-hunt-ban-eu476.html.

- ↑ "?". http://www.ens-newswire.com/ens/jul2009/2009-07-27-02.asp.

- ↑ EU takes aim at Canada, bans seal products, Associated Press, May 5, 2009

- ↑ 116.0 116.1 "EU ban looms over seal products". BBC. 2009-05-05. http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/europe/8033498.stm. Retrieved 2009-05-05.

- ↑ Murphy, Rex (21 August 2010), "A winning streak for international ignorance", National Post, http://fullcomment.nationalpost.com/2010/08/21/rex-murphy-a-winning-streak-for-international-ignorance/, retrieved 22 August 2010

- ↑ Independent Online. "IOL: Anderson adds her voice to chorus of protests". Int.iol.co.za. http://www.int.iol.co.za/index.php?set_id=1&click_id=31&art_id=qw1143581761520B253. Retrieved 2009-05-07.

- ↑ Post, National (2006-03-04). "McCartneys won't be charged". Canada.com. http://www.canada.com/nationalpost/story.html?id=3822bca5-58ba-45f6-91f6-d77fe99291c0. Retrieved 2009-05-07.

- ↑ "Sea Shepherd and Seal Defenders Take to the Streets". World-wire.com. 2006-03-13. http://www.world-wire.com/news/0313060001.html. Retrieved 2009-05-07.

- ↑ Press Releases & Media Attention about the Canadian Harp seal kill- Harpseals.org

- ↑ "''Jet'' and ''the Vines'' Fight to Save the Seals Music, movie & Entertainment News". Pr-inside.com. http://www.pr-inside.com/jet-and-the-vines-fight-to-r125551.htm. Retrieved 2009-05-07.

- ↑ Wenzel, George W. (1991). Animal Rights, Human Rights. University of Toronto Press. p. 47. ISBN 9780802068903. http://books.google.com/?id=g1l6pF0teV0C&pg=PA47&lpg=PA47&dq=%22harp+seal+question+is+entirely+emotional%22.

External links

Pro-sealing views

- Canadian Department of Fisheries and Oceans

- Canadian Sealers Association

- Defence by Editor of The Spectator

- Michael Harris, Ottawa Sun

- Sealing Industry Fact Sheet from Government of Newfoundland and Labrador

- Seán Ó Neachtain, Member of the European Parliament

- The Environmentalist's case for the Seal Hunt

- TheSealFishery.com

Anti-sealing views

- Anti Sealing Skybanner Campaign

- Atlantic Canadian Anti-Sealing Coalition

- Do Something!

- HarpSeals.org

- Help Stop the Seal Hunt-Help Promote Policy with Oceana.org

- HSUS Protect Seals Campaign

- IFAW: Seal hunt

- Respect for Animals Boycott Canada Campaign

- Scandinavian Anti-Sealing Coalition

- Sea Shepherd Conservation Society

Various

- A Response to the Canadian Department of Fisheries "Myths and Facts", by the Humane Society of the United States (HSUS)

- "Animal welfare and the harp seal hunt in Atlantic Canada", copyright and/or publishing rights held by the Canadian Veterinary Medical Association, site is maintained by the U.S. Government.

- Atlantic Canada Seal Hunt Myths and Realities, produced and/or compiled by Fisheries and Oceans Canada (DFO).

- Canadian Seal Hunt History website is part of the International Marine Mammal Association, inc. (IMMA)

- CBC Digital Archives – Pelts, Pups and Protest: The Atlantic Seal Hunt

- Harp Seal Info. & History, produced and/or compiled by Fisheries and Oceans Canada (DFO).

- History of World Fur Sealing (originally from Fahan School, Australia?)

- ICES/NAFO Working Group on Harp and Hooded Seals, International Council for the Exploration of the Sea (ICES)

- Internet Guide To International Fisheries Law, OceanLaw is an independent initiative focusing on international law of the sea and international fisheries law research, resource development and consultancy.

- Offshore/Inshore Fisheries Development – Harp Seal, Marine Institute of Memorial University of Newfoundland.

- Seal Hunt FAQ, CBC.

- Sourced Facts, news articles and opinion pieces on the Seal Hunt.

- The Seal Hunter – A seal hunting simulation game

- Transcript of a Larry King Interview with The McCartneys and Newfoundland Premier Danny Williams

News articles

- "Canada seal cull gets underway", BBC News.

- Canadian Press, "Seal hunt supporters in Quebec and Labrador confront animal-rights protesters", Ottawa Citizen, April 13, 2006.

- "Cute, cuddly, edible: Defending Canada's seal hunters", The Economist, 2 June 2008

- Paul McCartney urges the Canadian Prime Minister to stop the seal hunt, SpicyEdition.

- "Seal hunt helped us survive", Toronto Sun.

- "The shame of seal hunting", American Chronicle.

- Seal Sorrow: 90,000 Seals To Be Clubbed To Death by Michelle Theriault, The Huffington Post, July 6, 2009